DID CHOPIN QUOTE

HIS PREDECESSORS?

Beethoven

is reported to have found the character

of Don Giovanni in Mozart’s

eponymous opera repulsive. This

position derived from a view of

art that was based on a firm conviction

about its religious connotations,

as Dr. James H. Johnson points out

in his excellent article Sincerity

and Seduction in Don Giovanni¹.

Yet, consciously or unconsciously,

in the first movement of the Sonata

in c-sharp minor, Op. 27, no. 2 Beethoven

seems to refer very closely to one

of the central elements of Mozart’s

masterpiece: the First Act’s

murder scene, the beginning of a

turbulent series of events that lead

to Don Giovanni’s death.

The moon

is high. Don Giovanni breaks into

the house of the Commendatore with

the goal of adding his daughter,

Donna Anna, to his endless catalogue

of conquests. Trying to defend her,

the Commendatore engages Don Giovanni

in a duel and is fatally wounded. “Ah,

soccorso! Son tradito!” – he

screams – “L’assassino

m’ha ferito, E dal seno palpitante

Sento l’anima partir” (Help!

I have been betrayed! The assassin

wounded me, and from my palpitating

chest I feel my soul depart).² The

portrayal of this crucial moment

is one of genius in Mozart’s

hands. The accompaniment in triplets

played by the strings with pizzicati in

the bass relies on a pedal point

that creates strong harmonic ambiguity,

instilling a sense of agony that

will not resolve until the end of

the episode. The Commendatore’s

imploring vocal gestures are outlined

by insisting figurations sung by

both Don Giovanni and Leporello:

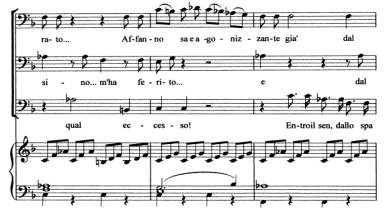

W. A. Mozart: Don

Giovanni, K 527, Act One, Scene One,

mm. 176-183

The likeness

between this scene and the first

movement of Beethoven’s

Sonata Op. 27, no. 2 is unmistakable:

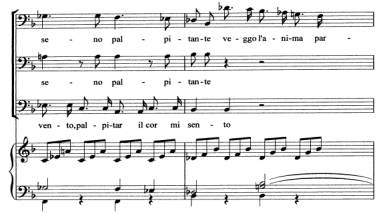

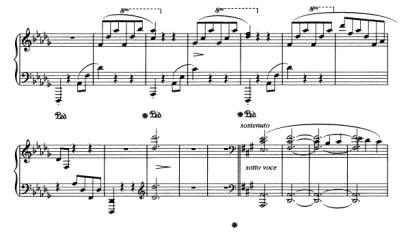

L. van Beethoven:

Sonata in c-sharp minor, Op. 27,

no. 2 - I. Adagio sostenuto - mm.

4-7

In Mozart, the calm ostinato of

the accompaniment portrays the silvery

quality of the moonlight. The sense

of mystery provided by the unassuming

stillness of the background establishes

a paradox with this tragic, fundamental

episode in the opera. While in Beethoven’s

opening movement of the Moonlight a

sense of tragedy being consumed might

not be perceived with equal power,

the color and texture achieved are

certainly suggestive of the nocturnal

atmosphere depicted by the accompaniment

in Don Giovanni’s scene.

Don Giovanni or not, it is the German

poet and music critic Ludwig Rellstab

who nicknamed the Sonata Moonlight.

The moon reflecting on Lake Lucerne

was supposedly the stirring image

about which Rellstab wrote in the

1830s, less than a decade after Beethoven’s

death.

To what extent

was Chopin influenced by this first

movement when composing his Nocturne

in c-sharp minor, Op. 27, no. 1,

written in 1835? Even though Chopin

was certainly unfamiliar with Rellstab’s

description of the Moonlight at the

time, doubtlessly there are strong

parallels that can be drawn between

the two pieces. Not only do they

offer nocturnal depictions: they

also share the same opus number,

key signature, accompaniment in triplets,

and dotted eighth-note rhythm in

the right-hand melody. Chopin occasionally

assigned this Sonata to his pupils,

and it would not be surprising that

introducing all these mutual elements

in his Nocturne had been a premeditated

decision on his part.

A recent

article by Dr. Nigel Nettheim shows

how Chopin’s Ballade

in f minor likely derives from material

found in works of Bach and Beethoven.³ Dr.

Nettheim drew parallels between the

elaboration of the thematic material

in the main theme of the Ballade

and the Prelude in b-flat minor from

the first volume of Bach’s Well

Tempered Clavier, and how subsequent

episodes in the Ballade clearly point

to specific melodic and cadential

components found in the same piece.

Elements from Beethoven’s Sonata

in f minor, Op. 57 seem also to have

deeply affected the coda of the Ballade

(perhaps not coincidentally in the

same key). The same article implies

that thematic material from the first

movement of this Beethoven Sonata

may have served as a model for the

closing movement of Chopin’s

Preludes, Op. 28:

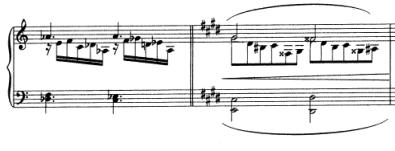

A comparison

between Chopin’s

Prelude in d minor, Op. 28, no. 24

(a) and Beethoven’s first movement

of the Sonata in f minor, Op. 57

(b) from Dr. Nigel Nettheim’s

article (with kind permission)

Striking similarities can be detected

between the works of Chopin and Mozart

as well. In the middle section of

the Largo from the Sonata

in b minor, Op. 58, for instance,

the eighth-note figuration unquestionably

resembles the writing in the B section

of Mozart’s a minor Rondo,

K.511:

Mozart: Rondo in a minor, K. 511

- m. 46 (left) / Chopin: Sonata in

b minor, Op. 58 - III. Largo - m.

77 (right)

How much

of it could have been unconscious?

A significant case was pointed out

by Ernst Oster, who concluded that

the reason why Chopin never published

the Fantaisie-Impromptu in c-sharp

minor (published posthumously as

Op. 66 by Julian Fontana) was that

it almost embarrassingly showed its

derivation and motivic manipulation

from the third movement of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata.�

THEATRICALITY

AND FORM IN CHOPIN’S

FANTAISIE, OP. 49

If composers

of the past deeply affected Chopin’s

works, whether or not accidentally,

we could hypothesize that in the

exposition of the Fantaisie in

f minor Chopin drew inspiration

from this same movement of the Moonlight.

A rather unorthodox approach to Sonata-form

was employed in this presto agitato,

where the second thematic block in

the exposition appears in the key

of g-sharp minor instead of following

a conservative route that would modulate

to the relative key of E Major. Beethoven

introduces a relation between themes

that is somewhat off balance, mirroring

the harmonic layout of a movement

written in a major key, where the

second thematic group conventionally

appears at the dominant. In this

movement, the dichotomy established

between the two thematic elements

is preserved, highlighting the structure

in a fairly conventional way. However,

the harmonic scheme introduces this

strongly ambiguous element, appropriately

justifying the piece’s subtitle Sonata

quasi una Fantasia in some of

its idiosyncratic design.

Between 1841 and 1842, Chopin completed

some of his greatest achievements.

The Ballades in A-flat major, Op.

47, and f minor, Op. 52; the Mazurkas

Op. 50; the Impromptu Op. 51; the

two Nocturnes, Op. 48; the Prelude,

Op. 45; and the Fantaisie Op. 49;

all these works were the result of

an extremely productive and inspired

period in which he enjoyed overall

good health, certainly stimulated

by the beautiful summers spent at

Nohant with George Sand. Despite

such a consistent level of quality

throughout those two summers, Chopin

failed to find satisfaction in his

Fantaisie in f minor. After months

endlessly spent refining it, with

reluctance he sent it to the publishers.

A few years

earlier, with the Ballade in g

minor, Op. 23, finished in 1835

and published in 1836, Chopin opened

the road to a new conception of Sonata-form,

with a new abridged version of a

structure that was feeling the burden

of time. It is commonly believed

that it took him nearly three years

to feel content with it (although

an unsolved mystery envelops the

gestation of the piece: based on

detective work done on the paper

that Chopin was using at the time,

some scholars concluded that it could

not have started any early than 1834).

Chopin found a solution to an otherwise

old-fashioned formula by eliminating

a full recapitulation: creating a

strong climactic point in the development,

he poured forth directly into the

second theme, bypassing the re-exposition

of the first thematic block. Soon

after the Ballade, this new convincing

intuition was captured again in the

first movement of the Sonata in b-flat

minor, op. 35. Chopin used almost

exactly the same identical procedure

in the opening movement of his third

Sonata in b minor, Op. 58, and ended

his life as a composer by sending

to the prints a work that represented

his final monumental effort, the

Sonata for Cello and Piano, Op. 65,

where the same concept was followed

once again in the first and fourth

movements. This innovative conception

had already been used in the 18th

century, but its occurrence was extremely

rare. We find an example of it in

the first movement of Mozart’s

Sonata in D Major, K311.

His two Piano

Concerti were a different matter

altogether. The stylistic blueprint

of the Classical Concerto with a

double exposition was pursued by

a nineteen-year-old who was trying

to affirm himself as an itinerary

virtuoso. Structural originality

was not an object. What are the motivations

that pushed Chopin to destroy a tradition

that had lasted for over sixty years?

Was it the fact that it became a

stale practice in need of a fresher

approach? Was he trying to create

a trademark that would set him apart

as a revolutionary, an iconoclast?

In

this respect, the Fantaisie Op. 49

somewhat represents a big anomaly

in Chopin’s output. After abandoning

the strict Sonata-form for nearly

a decade, Chopin resuscitated it

in the Fantaisie, presenting a configuration

that featured a full recapitulation

in a piece that, if living up to

its expectations, was supposed to

employ a free form! Yet, if the structure

recuperates old archetypes, what

needs to be considered ‘fantastic’ in

this case is the highly unconventional

harmonic layout, which presents a

fairly complex path. In the Fantaisie,

Chopin reaches heights never accomplished

before, embodying extraordinary qualities

drawn both from the present and the

past.

In Chopin’s

Fantaisie, Beethoven’s

revolutionary approach is preserved

and expanded in the exposition, where

the dialectic between the two thematic

groups is less radical because of

the melodic nature that unifies their

character. As the piece unfolds,

we also recognize traits that are

grounded in the operatic milieu:

there are two Marches, a Chorus,

a Recitativo. There is even an Intermezzo.

Furthermore, the harmonic layout

is based on relations of minor and

major thirds, playing a fundamental

role by evoking harmonic implications

often found in coeval Italian and

French arias. The Fantaisie was definitely

not an attempt to contribute to the

tradition of the Fantasia Drammatica,

a genre which Liszt and Thalberg

had introduced as of the early 1830s.

Chopin had kept himself rather distant

from that world, making brief, shy

appearances in it with the Duo

Concertante on Themes from Meyerbeer’s

Robert Le Diable for cello

and piano, written in 1831-32,

and, peripherally, with a Nocturne-like Variation

on the March from I Puritani by

Bellini of 1837, which found

inclusion as no.6 in Liszt’s Exameron.

In

the Fantaisie, transitional episodes

based on patterned arpeggiations

are used as linking elements between

sections and afford quite extravagant

modulations based on chromatic implications.

This kind of writing consents extreme

harmonic freedom and is stylistically

derived from formulas that most likely

Chopin employed in his improvisations.

It is in Eugene Delacroix’s

journal that we read about Chopin’s

extemporary playing being bolder

than his compositions, both in style

and character, his actual pieces

being mere distillations of his improvisations.

We surely find that boldness in these

arpeggiated figurations, virtuosic

in nature, whose inclusion in the

piece balances out the strictness

of the Sonata-form, re-establishing

contact with the idea of capriciousness

that one would assume to find in

a piece entitled ‘Fantasy’.

An

unexpected element occurred to me

only a few years after I had learned

the piece: the relation between the

austere opening in f minor and the

section in the key of B Major marked Lento,

sostenuto, which we could

define in operatic terms as an

Intermezzo. B breaks the octave

of F in two perfect parts, creating

a tension that surpasses that of

the simple dichotomy dominant-tonic,

frequently used to create harmonic

contrasts. It is the augmented fourth,

also known as tritone – Diabolus

in musica, as it was called

in the Baroque era. How ironic that

a tritone would distance this religious,

hymn-like Intermezzo from the severity

of the introduction! Stemming from

the Lydian mode and being a rather

common interval in Polish folklore,

one is only left wondering whether

this way of using the augmented fourth

in the Fantaisie was a coincidence.

I

mentioned how Chopin’s Fantaisie

embodies qualities that are drawn

both from the past and the present.

If stylistic elements were borrowed

from the contemporary Italian and

French Opera, form and balance link

the work to past traditions. In Chopin,

however, everything is in constant

transformation, even the reinvention

of a strict form as it was employed

in the 18th century. If the exposition

followed the harmonic structure found

in the third movement of Beethoven’s

Sonata, Op. 27, no. 2, the recapitulation

seems to backtrack to earlier years

and possibly follow the model presented

by the first movement of Mozart’s

Sonata in C Major, K. 545, which

features a recapitulation at the

subdominant. In Mozart, this procedure

was utilized conveniently, given

that the conciseness of the movement

did not allow much room for harmonic

and structural flexibility. In the

Fantaisie, the form is extended to

the degree that this route would

be completely unnecessary. Proposing

a literal recapitulation at the subdominant

(b-flat minor) led to the placement

of the correct tonal area (f minor)

for the second theme. However, because

of the modulation to its relative

major in the exposition, this made

the piece end in the ‘wrong’ key – A-flat

Major. Chopin had experimented with

a similar formula in the Scherzo,

Op. 31, where nonetheless the b-flat

minor of the opening plays such a

secondary role throughout the outer

sections that the relative major

prevails and imposes itself as the

featured key.

HARMONIC TENSIONS

While considering

the tritone relation employed in

the Fantaisie between the main

body of the piece and the ‘Intermezzo’ in

B Major, it occurred to me that a

similar strategy is utilized in the

Ballade in g minor, Op. 23. The scheme

is ingenuously articulated, with

a mirror-like architecture that bases

its pillars on three fundamental

keys:

g minor - E-flat

Major - (a minor) - A Major - E-flat

Major - g minor

The abridged recapitulation

pours forth into the second theme,

re-proposing E-flat major with a

long peroration that leads to the

extended coda in g minor. The presence

of a tritone in the middle, breaking

the piece in two, enhances A Major

as an extremely remote place, furthering

the sense of anticipation as the crescendo to

the development, based on a pedal

point, builds up the dynamic tension

to the fortissimo.

We previously

saw how in the Scherzo in b-flat

minor, Op. 31 the opening key quickly

turns to its relative major, D-flat,

closing the A section. Unexpectedly,

the Trio opens in A Major, enharmonically

a major third apart, compromising

the assurance that relating keys

conventionally provide:

F. Chopin: Scherzo in b-flat minor,

Op. 31 – mm. 253-268

The key

of A Major abruptly modulates to

c-sharp minor, parallel minor of

D-flat Major. In this Scherzo, the

shifts to new keys are often harsh

and unexpected, making the spectrum

of emotions much more defined. I

believe not coincidentally, the introduction

of the key of E Major (dominant of

A Major) via its relative (c-sharp

minor) in the Trio is used to create

a harmonic tension that is based

again on a tritone relation with

the opening key of b-flat minor,

showcasing brilliant waltz-like passagework

that is reminiscent of the outer

sections.

In the Polonaise

Fantaisie in A-flat Major, Op. 61,

third relations are used throughout

the work, creating unforeseen harmonic

situations enhancing the dichotomy

between thematic materials. The key

of the second major idea, B Major,

is already presented enharmonically

as C-flat Major in the opening measure

of the piece:

F.

Chopin: Polonaise Fantaisie in A-flat

Major, Op. 61 - m. 1

The

startling opening in a-flat minor

allows Chopin to use C-flat Major

as its relative major key or its

mediant, establishing already a relation

of thirds within the first measure

by treating the tension either as

VI-I or I-III. B Major will also

be used as the key proposing a brief,

fragmented recapitulation. Following

the harmonic path presented at the

beginning, the first measure of the

recapitulation (m. 214) features

the key of D Major, a tritone apart

from the key of the opening:

F.

Chopin: Polonaise Fantaisie in A-flat

Major, Op. 61 – mm.

208-220

What

follows is a chain of harmonies that

certainly implies a close relation

(A Major in measure 215 as the dominant

of D Major in the previous measure,

and C Major in the same measure as

the dominant of f minor in measure

216), but that are introduced in

a scattered manner, producing a state

of melancholy and desolation caused

by kaleidoscopic changes of colors

in pianissimo,

with a sudden forte urging

from the abysses (m. 215), immediately

vanishing into thin air.

Creating

striking harmonic contrasts was a

device used already in the 18th century,

mostly to create strong shifts in

color between movements of large

works. This is present early in Beethoven’s

output: in the Trio in G Major, Op.

1, no. 2, the Adagio movement is

in E Major; in the Sonata in C Major,

Op. 2, no. 3, the second movement,

Adagio, is also in E Major, distancing

the listener from a predictable relation

of dominant or subdominant. The same

procedure is adopted in his Piano

Concerto in C Major, Op. 15, where

the middle movement is in A-flat

Major. In the Piano Concerto in E-flat

Major, Op. 73, the second movement

is written in B Major (enharmonically

C-flat, a major third below E-flat).

Beethoven brings this dialectic even

further by using it within the first

movement of the Sonata in C Major,

Op. 53, where E Major appears in

the exposition as the key of the

second thematic group. The same operation

is used in his last Sonata, Op. 111,

where the second theme in A-flat

Major in the first movement is based

on a dominant pedal point. In the

Piano Concerto in G Major, Op. 58,

after a brief, intimate five-measure

introduction of the piano ending

at the dominant, the orchestra introduces

the same material, this time in B

Major.

Haydn

had started using this approach a

few years earlier: in his Trio in

G Major, Hob. XV/25, the slow movement

is in E Major (a possible harmonic

model for Beethoven’s

Trio Op. 1, no. 2?); in the Sonata

in c-sharp minor, Hob. XVI/36, the

middle movement is scored in A Major.

Years later, Haydn brings this practice

to an extreme in his Sonata in E-flat

Major, Hob. XVI/52, by writing the

middle movement in the far key of

E Major, emphasizing a strong attraction

to an ideal Neapolitan harmony found

already in the recapitulation of

the first movement.

Coloristic

shifts between movements of a large

work are present in Chopin as well:

the Scherzo from the b minor Sonata,

Op. 58 is in E-flat Major (enharmonically

D-sharp, a major third away from

B), a key that was already introduced

momentarily in the first movement

in the bridge between the two thematic

blocks of the exposition, functioning

as a pseudo-Neapolitan of the second

subject in D Major. The appearance

of E-flat Major again in the fourth

movement of this Sonata confirms

Chopin’s

astute layout of harmonic schemes

for extended structures, a skill

doubted for a long time by many opinionated

scholars who discussed Chopin’s

handling of large forms. Curiously,

in the Sonata in b minor, the dominant

of the main key (F-sharp Major) is

avoided throughout the entire work

as a main harmonic center, with the

exception of a brief momentary appearance

as the featured key in the first

appearance of the second theme in

the Rondo-Sonata movement.

Robert Schumann also used relations

of thirds to create paths within

multi-movement compositions. Kreisleriana,

Op. 16, comes to mind, where a chain-like

structure is superimposed to a sequence

of third relations: the opening movement,

in d minor, proposes a middle section

in B-flat Major; the same key is

used for the second lyrical movement

of the set; the second Intermezzo

of this movement is in the key of

g minor, which is also the key of

the following movement; the middle

section re-proposes the key of B-flat

Major, which is also the opening

key of the fourth movement; the middle

section is in B-flat Major, but features

a strong attraction to g minor, the

key of the fifth movement. The chain

pattern continues uninterrupted until

the end, and the set will even find

a sense of unity with the opening

by echoing the d minor of the Prelude-like

movement in the second Intermezzo

of the concluding piece. Schumann

extensively uses third relations

between movements of large works,

such as in the Fantasie in C Major,

Op. 17, with the second movement

in E-flat Major. The Piano Concerto

in a minor, Op. 54, features the

key of F Major for the second movement.

In Chopin’s Barcarolle, Op.

60, the relation of thirds is certainly

employed, but here the harmony shifts

by using substantial mode changes.

The opening key of F-sharp Major

is preserved quite consistently throughout

the first few pages, with somewhat

conventional transitions to its relative

minor (a minor third below) and its

dominant. F-sharp Major suddenly

turns into f-sharp minor, justifying

the sudden shift to its relative,

A Major (a minor third above), which

becomes the predominant key for a

substantial portion of the piece.

Through an extended section that

features some harmonic instability,

we land in C-sharp Major, beginning

a long peroration that returns to

the key of F-sharp Major (C-sharp

Major being its implied dominant).

This procedure seems to be relatively

simple, yet it reveals a carefully

planned scheme that supports the

Barcarolle’s unmistakable folk

implications. This simplicity also

reveals Chopin’s affinity to

operatic archetypes consistently

found in his works: the duet-like

melody in thirds and sixths (perhaps

a model for Sous le dôme épais,

the Flower Duet from Delibes’ Lakme?)

and the sudden modulations to relative

or parallel keys. The section marked sfogato might

also give us a glimpse of operatic

allusions, where the writing is reminiscent

of vocal qualities typical of the soprano

acuto.

SFOGATO?

Playing Chopin’s Barcarolle

for Russell Sherman radically changed

my vision of the piece: he encouraged

me to find the identity of the alto

voice, insisting that it was a much

needed element in the enunciation

of the melody, so as not to attribute

all the ‘responsibilities’ to

the soprano. “Chamber music”,

as Sherman would describe it, referring

to the timbric independence of each

line as of that of instruments of

different nature. Crucial to my understanding

of this essential factor was time:

only after years did I feel gratified

by the degree of confidence that

I had achieved in performance.

Another revelation

about the piece came when Sherman

asked one day, “Roberto,

since you are Italian… what

exactly does sfogato mean?”.

I mumbled “Being able to finally

say or do something after keeping

it inside for a long time”.

That was the closest paraphrase of

the term I was able to offer,

as I had never paid much attention

to a possible translation of it.

Looking somewhat puzzled, Sherman

proceeded to illustrate his account

of it, which was closer to “sfocato” -

in Italian, ‘out of focus’. “In

a mist”, he suggested, given

the silvery sound he so magically

produced.

A few days

later, I was leafing

through André Gide’s Notes

on Chopin, which I

had read somewhat superficially as

a teenager. Gide compared Chopin’s

works to Baudelaire’s Fleurs

du mal, assigning a whole new

meaning to the word sfogato and

its interpretation in this specific

instance:

Has any other musician

used this term, felt the desire,

the need to indicate this breathing

openness, this breeze which, interrupting

the rhythm, intervenes unexpectedly

to refresh and perfume the middle

section of the Barcarolle?

I was perplexed. Chopin was the

first composer ever to employ the

word sfogato in a score,

but I found the idea that he

might have misused it tempting. The marking,

which appears in measure 78, has been

puzzling many, and unless Chopin

confused sfogato with ‘sfocato’,

I found difficult to believe that he would

get so descriptive of such an intense,

emotional state:

Example P.8 - F.

Chopin: Barcarolle in F-sharp Major,

Op. 60 - mm. 77-85

Certainly, ‘in

a mist’ is a

plausible interpretation. Perhaps

Sherman had a point. Maybe Chopin

just misspelled an Italian word,

hearing it pronounced by Countess

Carlotta Marliani in her colorful

Tuscan accent, where hard Cs seamlessly

turn into guttural Gs. Nevertheless,

I was quite keen on the notion

that Chopin had something in mind

that differs from what we normally

imagine in this passage. Perhaps

he borrowed the word from a common

vocal term that indicates a very

high acrobatic soprano voice,

with light, airy tone - the

so called soprano acuto sfogato.

In his youth, Chopin had used other

vocal terms in his pieces in order

to suggest an emotional state. Is sfogato a

possible allusion to the lightness

and airiness of the passage? To be

played in the style of a soprano

acuto sfogato? Did André Gide

have it right?

I recently looked

up sfogato on

the internet. Here is what I found: ‘Unburdened’,

which somehow made a strong case,

especially in light of the harmonic

function and the emotional release

of that specific passage; ‘Relieving

the heart with the utmost expression’ (courtesy

of the Dutch Piano Duo Sfogato),

which was certainly better than

the translation I had provided for

Sherman: it aptly serves the

nature of the dolce that

accompanies the melody, giving

its intonation a full, inebriating

quality, floating on the rich

texture of overtones generated by

the left hand. I am still not completely

certain that Chopin used the word

being fully aware of its meaning.

Certainly, the Piano Duo Sfogato provided

an accurate translation of the term –or

at least the closest one.

õ õ õ

Some months ago, my friend Valerie

provided quite a wonderful description

of the Barcarolle (and the sfogato passage),

which I will selflessly share:

“Chopin wrote

to his family in July 1845:

‘I hope Paris

will have good weather for this month’s

celebrations. This year [...] it

is to be illuminated. On the Seine,

this summer, speculators in human

whims have hit on a new notion. There

are several vessels, very smartly

got up, and gondolas in the Venetian

style, that ply in the evenings.

This novelty delights the boulevard

crowds, and it is said (I have not

seen it myself) that great numbers

of persons go out on the water’.6

The idea of writing

a Barcarolle came to Chopin around

this period. It is a rich, multi-voiced

work, where contrapuntal ideas are

brought to such a new level that

one needs to re-evaluate the concept

of measure as a restraining factor.

There are instances, such as in the

section marked dolce sfogato,

where Chopin introduces a voice in

the left hand which, by means of

subterranean devising, manages to

descend while remaining virtually

outside of the measure, as if it

were sinking gossamer, delicately

masked by voluptuous meanderings

in the right hand, nevertheless reaching

us on a subconscious level.

Rare is the interpreter who can find

all of the voices in the Barcarolle

and give them more than effective

pianism, but arrive at the sort of

feelings which these interwoven lines

are intended to evoke. It is

a monumental achievement on many

levels. Friederich Nietzsche, whose

heart had room for music, considered

the Barcarolle Chopin’s best

work.

Everything is here: the heave, the

ripples, the glints and shadows,

the imagined whiff of canals and

gondoliers alike, a playful suggestion

of danger, of sense of unity between

sensuality, intrigue, rightness and

joy. Its cosmic quality lifts us

into a sublime, suspended, blissful

state, not quite as a loss of innocence

but as the most delicate hint of

the possibility: civilized consummation

through non-consummation – a

state of eternal postponement – of

dwelling at the brink end, settling

for that as an end in itself”.

Valerie also pointed out that “Chopin

had a head for numbers. He would

have been amused to learn the price

of a gondola today: between

fifteen and twenty-five thousand

U.S. dollars!” [That was before

the conversion to Euros and the tragic

fall of the dollar]

1) James H. Johnson, “Sincerity

and Seduction in Don Giovanni”, “Expositions”,

Vol. 1, no. 2, Fall 2007 (September),

49

2) Translation by Roberto Poli

3) Nigel Nettheim, “The Derivation

of Chopin’s Fourth Ballade

from Bach and Beethoven”, “The

Music Review”, Vol. 54 No.

2, 1993, 95-111

4) Ernst Oster, “The Fantaisie-Impromptu:

A Tribute to Beethoven” from

Aspects of Schenkerian Theory (New

Haven: Yale University Press, 1983),

Appendix, 189-207; original article

published in Musicology 1 (1947),

407-429

5) André Gide, Notes sur

Chopin (Paris, France: L’Arche,

1948), 31 - Roberto Poli, translation

6) Ethel Lillian Voynich, Henryk

Opienski, Chopin’s letters (Mineola,

NY: Dover Publications, 1988), 289

|